Space Leadership Comes Before Selfies

Leadership

December 14, 2017

Paula Kiger

Topics

Authentic, Leadership, Self Development, Values, VisionI have had three opportunities to participate in “NASA Socials,” gatherings of selected social media aficionados to help tell NASA’s story.

Two of those NASA Socials took place at Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, FL. Both times, KSC Director Bob Cabana stopped in to greet us. At one of the visits, he grabbed his phone and took a fun selfie with our group.

When you meet a leader like Bob Cabana and have a quick, fun “social media moment,” it’s easy to be lulled into thinking “gosh he makes leadership look easy.”

It was when I read Mike Massimino’s book, Spaceman: An Astronaut's Unlikely Journey to Unlock the Secrets of the Universe, that I was reminded that the road to leadership is about much more than a smiling public face.

In Bob Cabana’s case, he demonstrated leadership during one of NASA’s darkest moments, long before selfies existed.

Leadership After the Columbia Disaster

Massimino was close friends with the crew of Mission STS 107, which flew the Columbia shuttle but did not return successfully. In fact, it was a timing issue that led his Mission, STS 109, to “jump in line” ahead of STS 107 to fly Columbia to repair the Hubble Space Telescope.

As events unfolded after the STS 107’s disintegration during re-entry, Massimino joined his fellow astronauts in trying to figure out what to do. Some consoled. Some investigated.

What did Bob Cabana, serving as the deputy chief of Johnson Space Center at the time, say? Massimino writes:

“He confirmed what we already knew, that the crew had been lost. He said, ‘This is a terrible day for the astronaut office. This is going to be one of the worst days that any of us will ever have in our lives. But we’ve got to get through it. The families are on their way back from Florida. As devastated as we are, just imagine how they’re doing. The first order of business is to take care of them.”

Loving What You Do

I know there are plenty of experts out there (Cal Newport, for example) who argue that being “passionate” about your career choice isn’t necessary to perform well, but I tend to disagree.

For Mike Massimino, the passion started at age 7 when Apollo 11 landed on the moon. Over the course of his career, he made some decisions about academics and career moves that placed him, ultimately, in exactly the right position. Learning human factors would possibly have been seen as a mistake in a profession populated by fighter pilots, but choosing that course of study led to him being the designer of a display critical to moving the shuttle’s robot arm easily and accurately.

Leaders Never Stop Developing

After Massimino’s first extravehicular activity (EVA), he wondered why he wasn’t getting mentioned more as a candidate for the next one. The answer? He was following, and not leading.

In Canada, Massimino had to walk across a lake – not just any “walk across a lake” – an hours-long hike in the most frigid of weather, in the dark. He was terrified at the start. Mid-hike, he says:

“The whole trip changed for me halfway across that lake. The conditions hadn’t changed, but my mind-set had, and that’s what expedition training is for. I started to enjoy what I was doing. I started to appreciate the opportunities to learn new things, and the days flew by.”

Leaders Tackle the Unknown

You know what Mike Massimino was the first astronaut to do?

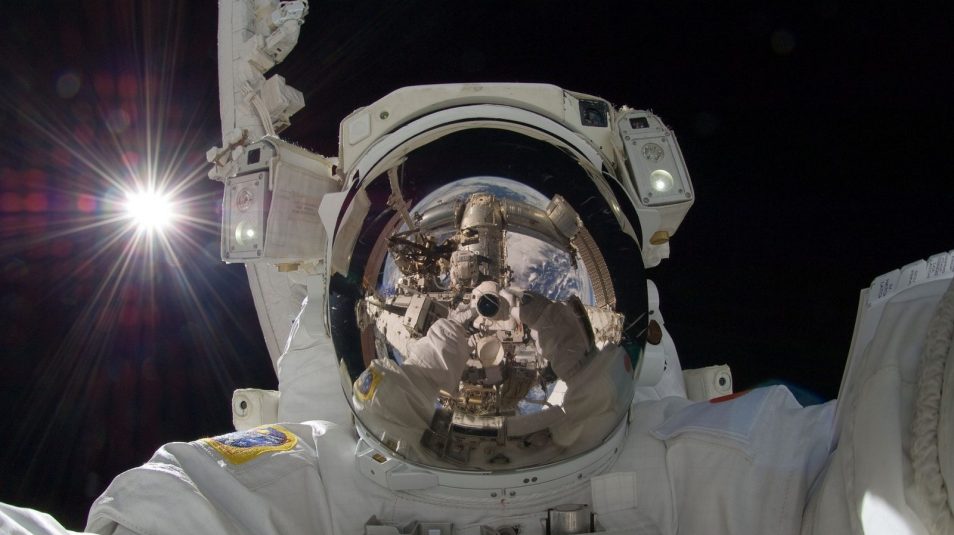

He was the first astronaut to tweet from space. Can you imagine how foreign tweeting must have seemed back in 2009? But he did it, and it changed his world, made him exponentially more recognizable, and helped him indulge his passion for explaining space.

I imagine Bob Cabana may have had his doubts the first time he flipped a phone around for a selfie too, but he earned the privilege of helping spread the good news about space by having the courage to lead his team through the difficult times.